Youra Livchitz

, ermordet am 2. Juni 1943

Acryl auf Leinwand

70 x 100 cm

entstanden 04.2010

Ihre Widerstandsaktion war mehr als spektakulär: Ausgestattet mit gerade mal drei Kneifzangen, einer roten Sturmleuchte und einem Revolver überfallen drei junge Belgier 1943 einen Deportationszug, der von Mechelen nach Auschwitz unterwegs ist.

Willy Berler, ein Überlebender

von Auschwitz, über die ungewöhnliche Tat im besetzten Belgien:

"Ich glaube, dass der Überfall auf den 20. Transport eine der größten

Widerstandsaktionen überhaupt war."

Drei Leute mit einer Laterne und einem Revolver, die einen gut bewachten

deutschen Transportzug aufhalten wollen, dazu gehört mehr als Mut,

dazu gehört Tollkühnheit.

Der Zug, den Youra Livchitz mit zwei Kameraden des belgischen

Widerstandes auf offener Strecke bei Brüssel stoppte, war mit mehr

als 1630 Juden an Bord nach Auschwitz unterwegs. Die Soldaten im ersten

und letzten Waggon waren von der waghalsigen Befreiungsaktion völlig

überrascht. "Wir hatten ein irres Glück", erinnert sich Maistriau,

einziges noch lebendes Mitglied des kleinen Kommandos vom 19. April 1943.

"Heldentat wider alle Vernunft"

An den Jahrestag dieser einzigartigen Aktion, der auch den Beginn des

Aufstandes im Warschauer Getto markiert, wird jedes Jahr in dem kleinen

Ort Boortmeerbeek bei Brüssel in der Woche nach Ostern erinnert.

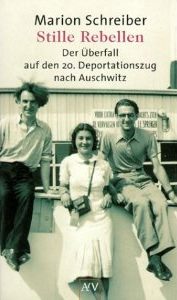

Gedacht wird einer "Heldentat wider alle Vernunft", wie die Autorin Marion

Schreiber "dieses lebensgefährliche Abenteuer" der drei jungen Männer

in ihrem Buch "Stille Rebellen" einordnet.

Belgiens kommunistische Résistance hatte bereits erwogen, einen

Deportationszug der Nazis zu stoppen und die Insassen zu befreien, wie

Maistriau später erfuhr. Doch dann habe die Gruppe diesen Plan als

zu gefährlich fallen lassen. Youra Livchitz, Robert Mastriau und

Jean Franklemon jedoch radelten am Abend des 19. April 1943 vor die Tore

Brüssels, stellten eine rote Laterne auf die Gleise und lauerten

auf den Transport aus dem belgischen Konzentrationslager Breendonk.

Der Zug kam. Er hielt. Und Livchitz öffnet den Waggon, der vor ihm zum Stehen gekommen war. Fast 60 Menschen waren in den Güterwagen gepfercht. Zwei Frauen sprangen als erste heraus, eine Handvoll Männer folgte. "Aber ein Mann wollte die Leute davon abhalten herauszuspringen", erzählt der Befreier. 17 Menschen verließen den Waggon schließlich und brachten sich im nahen Wald in Sicherheit. Aus dem Waggon nebenan hörte Maistriau Stimmen: "Öffen Sie! Öffnen Sie!" Doch da rollte der Zug schon wieder an.

"Insgesamt flüchteten 231 Deportierte an diesem 19. April 1943 vor der deutschen Grenze aus dem Konvoi", recherchierte Schreiber. "23 Juden starben bei dem Fluchtversuch unter dem Kugelhagel des Begleitschutzes oder durch einen unglücklichen Sturz." Doch alle Entkommenen hätten auf die Hilfe der belgischen Bevölkerung rechnen können - so wie Paul Spiegel, heute Vorsitzender des Zentralrates der Juden in Deutschland.

"Wer ein Menschenleben rettet, der rettet ein ganzes Volk"

Als Zweijähriger war Spiegel mit seinen Eltern auf der Flucht vor den Nazis nach Belgien gekommen. Seine Schwester Rosa wurde zusammen mit 130 anderen Kindern im 14. Deportationszug aus Belgien nach Auschwitz gebracht, Paul überlebte bei freundlichen Bauern in Chapelle-lez-Herlaimont. Die Bedeutung des Überfalls auf den 20. Deportationszug unterstreicht Spiegel mit einem Spruch aus dem Talmud: "Wer ein Menschenleben rettet, der rettet ein ganzes Volk."

Quelle: http://www.stern.de/politik/geschichte/widerstand-der-tollkuehne-ueberfall-auf-einen-todeszug-535522.html

_________________________________________________________________________

The heroes of Mechelen

Equipped with only a lamp, pliers and a pistol,

these three young men rescued hundreds of Jews from a train heading for

Auschwitz and almost certain death. Robert Maistriau, the last survivor

of the... The whole thing took perhaps half an hour 60 years ago. But

Robert Maistriau has never forgotten that moonlit night on a Belgian railway

line in April 1943 as he scrambled to open the doors of a cattle truck

and urged the terrified Jews inside to get out and run away. Shots rang

out from the German guards, but in the confusion 17 prisoners escaped.

Later, further down the track, 200 more managed to flee. The unlucky 1,400

left on the train reached their destination: Auschwitz. Few lived to tell

the tale.

Maistriau, now 82, is the last survivor of an extraordinary act of wartime

resistance to the Nazis. The train he stopped, with two friends, was the

20th convoy transporting Jews from Belgium to the infamous extermination

camp in Poland, where more than a million were gassed. It was a rare red

light for genocide.

Equipped with pliers, a hurricane lamp and a single pistol, the three

executed a plan that had been rejected by organised partisan groups as

too dangerous. Their improvisation and derring-do owed much to the scout

troops where young Belgians, in those pre-TV days, spent much of their

spare time. The intrepid trio even made their getaway by bike. But it

was no Tin Tin adventure: resistance activity or possession of a gun was

routinely punished by death, often after torture.

Maistriau, who today has failing eyesight and a bad leg but a still-sparkling

sense of humour, recalls that their key item of equipment was some red

tissue paper he filched from his mother's drawer at home. That covered

the hurricane lamp and brought the train to a screeching emergency halt

on a bend in the track east of Brussels. "I can still remember the noise

of the brakes," he says.

The attack on the convoy - by coincidence the same day the doomed Warsaw

ghetto uprising began - is widely known in Belgium. But it took a German

writer, Marion Schreiber, to weave the episode into the wider context

of the war, the German military administration, the SS and Hitler's "final

solution" in her fascinating book, Silent Rebels.

Maistriau's baptism of fire could have been any kind of sabotage operation.

But three days beforehand his schoolfriend and croquet partner, Youra

Livchitz, a Russian-born Jewish doctor, told him of the plan. "He said

there would be a train taking Jews to Poland. It's difficult to say now

exactly what we knew then. We knew they were badly treated, but we didn't

know exactly what was going to happen to them. Livchitz didn't know either."

It takes a leap of the imagination to connect the Brussels of today with

the Nazi-occupied capital of the 1940s. In 2003, Avenue Louise, half Park

Lane, half Knightsbridge, is home to sleek EU lobbying firms and multinational

corporations. In 1943 it was the site of Gestapo headquarters, strafed

with stunning precision that January by a Belgian pilot serving in the

RAF. Django Reinhardt was all the rage and the black market was booming.

Starting in 1942 Belgium's Jews were rounded up and taken to a barracks

at Mechelen, dubbed "the ante-chamber of death". From there, meticulously

numbered for the SS files - and the historical record - they went straight

to Auschwitz. Thousands of others, including children, fled or went into

hiding, sheltered by brave non-Jews at enormous risk. Those who dared

go out without wearing the obligatory yellow star were frequently spotted

by a Polish Jewish informer working for the Gestapo.

Belgium has its wartime skeletons, including Flemish and Walloon volunteers

who fought with the Nazis. But the statistics of mass murder tell the

story: 50% of its 56,000 registered Jews survived the occupation. Next

door in the Netherlands, where Anne Frank came to symbolise the human

face of the holocaust, the figure was just 12%.

People reacted differently to the strain of life under occupation. "Often

there is only a very thin line between commitment to collaborationism,

to resistance or to Gaullism," the historian Richard Cobb has written

of France. "One should not exclude the elements of luck and chance, especially

in the lottery of wartime that puts a special premium on unpredictability

that may hand out, with equally blind impartiality, the winning number

or the tarot card of death."

Maistriau's fate was written in his family. His father was liberal and

anti-clerical. His mother's first husband was a French Jew, killed in

the Great War. And there were Jewish friends - Livchitz and others - in

the scouts and at school. He was bored with his desk job in a metals company,

impulsive, and prepared to fight the Germans, still hated for their atrocities

in 1914. "I wasn't crazy, but I was very easily carried away," he explains.

"And I was ready to take risks."

Livchitz, slightly older, was a charismatic figure still remembered vividly

by contemporaries. He was caught months after the attack and executed

as a "communist terrorist", refusing to wear a blindfold as he faced the

firing squad. The third member of the group was Jean Franklemon, an art

student and communist, who was sent to a concentration camp but lived.

Bureaucratic efficiency helped reconstruct this terrible story. Train

801 had 30 trucks carrying 1,631 Jews. The oldest deportee, Jacob Blom,

number 584, was 90. The youngest, Suzanne Kaminski, number 215, was five

weeks. A few, alerted to the escape plan by the resistance, had managed

to saw though bars and doors and were ready when the train stopped. Most

of the others were too frightened or weak.

Maistriau describes how he cut the wire securing the door of one truck,

shouting "Sortez, sortez," and the wry humour of what followed. "What

do you expect us to do now," one anxious woman asked him, looking round

in dismay at the dark and trees. "I said: 'Madame. Brussels is that way,

Louvain is that way. Sort it out for yourselves. I've done all I can.'

But they all made their way safely back to Brussels."

Emboldened by the raid, other Jews escaped when the train resumed its

journey, though some were injured or killed by the fall or the guards'

bullets. Simon Gronowski, 11 at the time, still remembers the last words

his mother spoke to him in Yiddish as he jumped off: "The train's going

too fast." He never saw her again.

Maistriau continued working with the resistance but was captured in 1944,

deported to Buchenwald concentration camp and finally liberated by the

Americans. He spent the rest of his working life farming in Congo, staying

on after independence.

Years later he was recognised as a "righteous gentile" by Israel's Yad

Vashem holocaust centre for helping persecuted Jews. And there were meetings

with survivors or their children at ceremonies commemorating the heroism

of that long-ago night. "At one of them," he says, sounding bemused, "a

woman came up to me and kissed me, and said: 'You saved my life.'"

· Silent Rebels: The true story of the raid on the 20th train to

Auschwitz by Marion Schreiber, is published by Atlantic Books on June

24

http://www.buzzle.com/editorials/6-19-2003-41883.asp